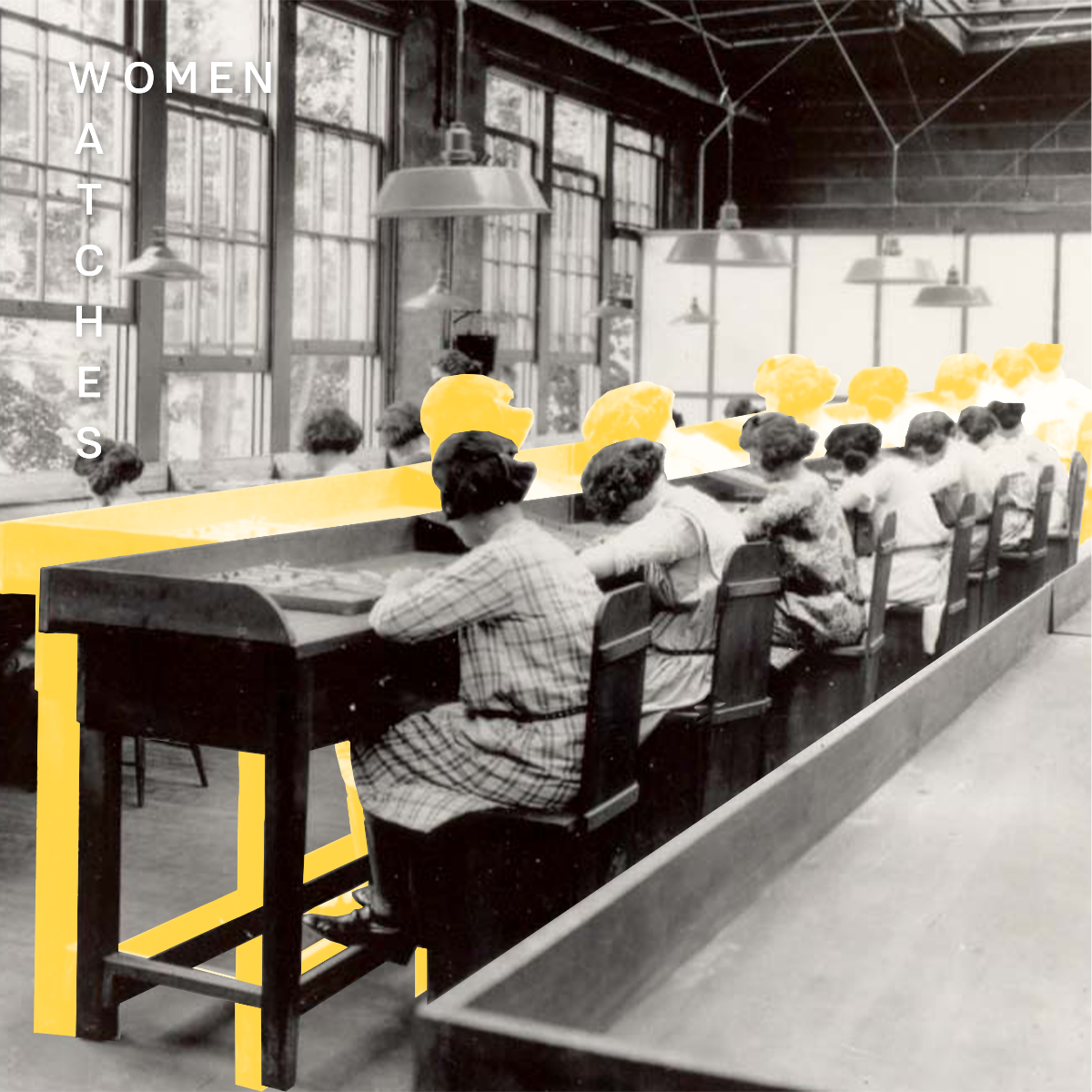

Are women the unsung heroines of the history of watchmaking? Several recent academic publications have gone some way to establishing the role women have played in the Swiss watch industry, performing often thankless, sometimes dangerous, rarely acknowledged yet crucial tasks. Estelle Fallet is chief curator at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Geneva. In an article titled Women in the Workshop, she notes that in France and in England, women were not permitted to work in watchmaking until 1785 whereas “as from 1690, women were admitted to the Geneva watchmakers guild, established in 1601. They were employed in tasks such as making the chains for fusée mechanisms or chasing balance cocks. They also finished screws, hands and hinges. Women brought precision, dexterity and, most importantly, rapidity to their work.”

The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains”

The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains” . The indispensable “petites mains”

The indispensable “petites mains”

by Christophe Roulet

Since watchmaking’s industrial revolution, women have filled half production jobs. Many of these workers come from outside Switzerland and not all the tasks they once performed were without risk…

Equal numbers, separate workshops

A first step towards admitting women into the profession was made in 1843 with the opening of the first watchmaking school for young girls, in Geneva. But this would be a slow process; in Saint-Imier, for example, girls were excluded from the town’s watchmaking school until 1910. Because of their perceived patience and dexterity, women were natural candidates for the meticulous task of adjusting escapements, on which the watch’s precision depends. Often this was the job of home workers. By the end of the nineteenth century, women made up around a third of the Swiss watch industry’s workforce, as Estelle Fallet observes: “In the watchmaking regions, a good mother was one who worked in a fabrique to provide for her children’s future. Watchmaking enabled women to reconcile home life and working life. From the 1920s, the Swiss watch industry employed as many women as men, although workshops were not mixed.”

Swiss historian Stéphanie Lachat, who was recently appointed co-director of the Federal Bureau for Equality, has focused part of her research on the women who largely contributed to the success of the Swiss watch industry from its earliest days. Quoted by an article in The New York Times, she explains how “the female workforce at the factories were pioneers. This was the first time so many women could have an intensive professional life that was accepted by society. Of course, given the times, they also remained the mother and the wife, taking care of the children and the household. This double duty moved up the social ladder to include bourgeois women and also spread to other industries.” These Pionnières du Temps — “the pioneers of time”, the title of Dr Lachat’s thesis which examines the period between 1870 and 1970 — were the first to demonstrate that employment outside the home was compatible with family life.

Poisoned by radium

Pioneers or not, women were considered a source of cheap labour. They were the “petites mains”, an army of workers, often paid per piece. Many were recruited to apply luminous paint to watch dials and hands. First used in Switzerland in the 1910s, this paint was radium-based (discovered by Marie Curie in 1898, radium was, astonishingly, promoted as having multiple health benefits). Between 1918 and 1963, thousands of these so-called “radium girls” were encouraged to lick the end of their brush to a fine point before applying what was a radioactive substance. Switzerland does not maintain records of the number of women who developed a cancer as a result of this practice, nor was there any public outcry. In the United States, it would be a different matter.

It took the tenacity of one woman, Grace Fryer, to bring their case to public attention. Like four thousand of her compatriots, Grace Fryer was hired by one of the American firms supplying the country’s watch factories to apply radium-based luminous paint to dials. Despite its radioactive nature, they were given no protective clothing nor instructions as to the type of product they were using on a daily basis, with devastating and sometimes fatal effects on their health. When the first women filed complaints against their employer, management went to great lengths to discredit them, even pressurising doctors into attributing deaths to syphilis. Undeterred, in 1927 Grace Fryer and four other workers filed a lawsuit against U.S. Radium. Their story prompted a wave of indignation in the United States. But the wheels of justice turn slowly and it would be more than a decade before the courts ultimately ruled in their favour, in 1939. Grace Fryer died in 1933…

Across the border

Switzerland’s watch industry thus remained competitive largely thanks to a female workforce whose skills, though never openly acknowledged, were widely recognised. Many of these women arrived in Switzerland from other countries, especially Italy, and would play a decisive role post-World War Two. Francesco Garufo, curator at the Musée d’Histoire in La Chaux-de-Fonds, is the author of a doctoral thesis on immigration and the Swiss watch industry between 1930 and 1980. Among the 90,000 people employed by the watch industry in the early 1970s, why were so many of the 20,000 foreign workers women? “Because they weren’t in competition with Swiss workers,” Dr Garufo explained to swissinfo.ch. “It was argued that they were employed only for a limited period; their income complemented their husband’s earnings; and they didn’t acquire specific skills and therefore did not present a risk of technology transfer. Also, they were paid significantly less, as were Swiss women. There was an average salary for qualified workers, another for semi-qualified and unqualified workers, and another for women.”

Francesco Garufo is adamant: recourse to foreign and specifically female labour “facilitated the modernisation of production methods. The local workforce had been trained in traditional techniques and had no interest in working on an assembly line. Recourse to foreign women workers made it easier to introduce the changes that would enable Swiss watchmaking to stay competitive.” What of the situation today? According to the latest figures published by the French office of national statistics (INSEE), Swiss watch companies employ 11,550 cross-border workers from the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region. This rises to 15,400 when including those with Swiss residency; equal to one fifth of the sector’s total workforce. And as in the past, women make up a large and essential part of their number.